By Ajay Rose

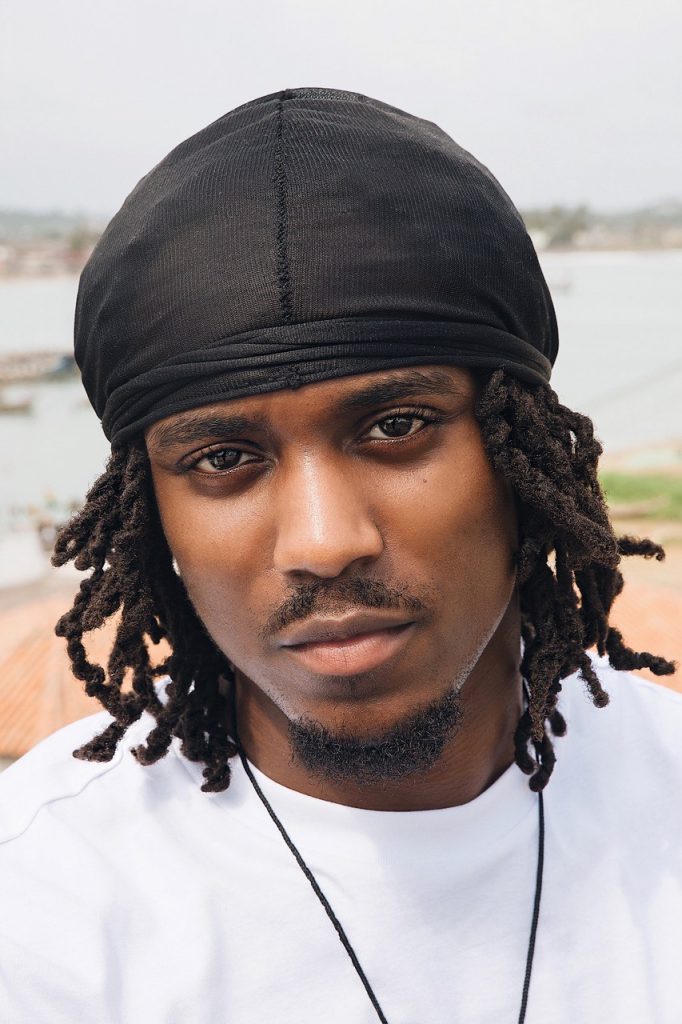

Casshh has been away for five years but his pen game stronger than ever…

Back in the day, if you wanted a new song on your phone, somebody had to send it to you via Bluetooth or infrared.

To send a song via infrared, you had to hold two phones next to each other so that they were touching. To get to a point where two people are willing enough to wait it out and hold two phones next to each other for 5-10 minutes, UK rappers had to not only create music but also find ways to market it.

In traffic, outside shops, in shopping centres, at youth clubs, pulling up at the park, wherever. Streaming platforms weren’t around, there was no Twitter or Instagram, YouTube was in its infancy and the music industry was not as receptive of UK rap like it is nowadays. Artists had no choice but to build their own infrastructure and trailblaze their own path. One of UK rap’s more under-appreciated pioneers is Cashtastic, a musician who gained widespread appeal for the honesty and vulnerability he displayed in his music.

Cashh had to release three joint mixtapes in order to get a Fire in the Booth aged 16, and from there, his buzz would continue to grow. When he dropped his ‘Alarm Clock’ mixtape in 2014, which featured the likes of Kano, Krept & Konan, G FrSh and Lady Leshurr, his years of grafting appeared to be on the verge of paying off in a big way. But shortly after this tape dropped, Cashief Nichols was removed from the UK for allegedly overstaying.

When Cashh arrived at the airport in Jamaica upon being removed, much like his music grind, he had no links and few people to rely on. He had no choice but to build a new life for himself while fighting his case for five years between 2014-2019, before returning to the UK as a citizen last year.

Since re-entering to the UK, Cashh dropped a powerful ‘Daily Duppy’ freestyle alongside a few singles, demonstrating his pen game is stronger than ever and reminding that, this time, Cashh is here to stay. Culture Mag caught up with Cashh to discuss his journey so far.

Talk about how your music career first started…

The first mixtape I ever dropped was a mixtape called ‘The Formula’. It was a joint mixtape with a good friend of mine called LP, we were just two yutes growing up in Peckham with the love of making music. That was the first step, I think I dropped that when I was in Year 7 or 8. On that tape, I think it was the first time I’d collaborated with Giggs. And locally, within Peckham, within South London, it did its rounds. Then from there, I did another joint project called ‘C and C’ with another artist called Chunkz. Then from there, I did another joint project called ‘Advanced Music’ with Yung Meth, and then went and did my first Fire In The Booth, at 16 years old with Charlie Sloth on BBC 1Xtra. Then from there, everything started looking up for me, in terms of the exposure. I did my Behind Barz on Link Up TV, then I dropped the mixtape ‘Lil Bit Of Cash’.

Your earlier music received a very strong response. I remember a lot of your tracks doing the rounds on Bluetooth/Infrared back in the day. Why do you think that was?

When I first entered the game, it was very much hardcore street rap, rapping about stuff that we were living, what we were experiencing on a day-to-day basis. What I managed to do was tap into a different side of it. It’s cool telling an audience how many different ways you can do something to somebody but no one was vulnerable enough to say things that could be deemed as embarrassing. I think that it was made me stand apart. For example, mentioning the fact I’ve been evicted from my house, mentioning the fact that my mother was doing time, at the time, in prison. Mentioning the fact that I’ve been robbed and just speaking from a different perspective because the reality is a lot of people go through these things. A lot of people go through these things but the majority only hear it from one side. Me being vulnerable in my music and just being an open book, helped me to elevate to another place. It also helped other artists later on down the years to become as comfortable saying things that may have been deemed embarrassing.

Nowadays music can spread easily through the internet. Talk about what the work you had to put in to promote music without being able to rely heavily on the internet?

We had to work for it. I feel like you don’t have to do as much work for it now. In order for me to even get a Fire in The Booth at 16 years old, I had to put out three mixtapes before Charlie Sloth even knew my name. In terms of doing a lot of joint projects, that came from me just being around the right places, just being hungry. The music took off because we weren’t relying on anybody. We had no links, so this was us just showcasing our talent and just stepping with our best foot forward. Hunger played a major role. Back then it tracks got sent via Bluetooth, and with Bluetooth, you literally had to be next to the person.

And with infrared you literally had to hold two phones next to each other…

Literally, you had to hold the phone next to it! The amount of time you’ve been sending a song on infrared and there’s maybe 5% left before you get it, then someone moves their phone and you gotta start again! It’s the hunger of being around, being about and being somebody people can relate to. Whereas now, someone can accidentally discover your music, yeah there are benefits of that, but because of how easy streaming platforms make it to discover new music, people aren’t out there as much. Nowadays it’s ‘I can just sponsor this post on Instagram and reach this particular area’, whereas back in the day, it was ‘I need to go the area and make they’re hearing my stuff’. And that’s what we were doing back then. Sometimes we’d be driving and just pulling up on people like ‘yo you got this new mixtape?’ You don’t need to do that anymore.

You signed a publishing deal with Universal Records back in 2013. How did that come about?

I had a publishing deal with Universal. I signed that deal around 2013. I’m very much about putting in the work, so I didn’t even announce it until like a year later. I completely forgot. For me, I saw it as ‘this is just half of the job, now I actually have to put the work in’. so by the time I announced it, was a year later.

What was the response like when you dropped your ‘Alarm Clock’ mixtape in 2014?

With Universal publishing, they’re not a record label, so that deal was signed more for my writing. So we dropped ‘Alarm Clock’ independently, but it was in and around the time that I signed my publishing deal. We had some great collaborations on there. If you go through the tracklist, it’s crazy. I tried to the collaborations in a way where people were working with people they hadn’t worked with before. I put Kano and G FrSh on a song, I put Lady Leshurr, Yungen, A Dot and myself on a song. I mixed and matched and did a song called ‘Your Biography’ with me, Krept & Konan, Wiley and Ghetts. I tried to put a body of work together that I felt the UK needed at the time. But unfortunately, I wasn’t able to push it, because as soon as I dropped the project, I ended up getting removed from the country.

How did you go from a position where you’ve just dropped a strong body of work, to one where you now have to leave the country?

You know what, it started from when I dropped my first mixtape. So this whole entire time, since you’ve ever heard of Cashtastic, I was fighting this case behind the scenes. For years and years, I’ve been going back and forth trying to fight this situation. What our case was fighting for was, me overstaying as a minor. I literally didn’t know. I migrated to the UK and joined my family over here. Even if I knew, at five or six years old, I couldn’t just book a ticket and leave. And that’s literally what I was trying to say to them, clearly, since I’ve been of age to be able to sort this situation out, there’s a paper trail that shows I’ve been trying to sort the situation out. You can’t judge me on a scenario I had no control over, as a five or six-year-old minor. And it just so happened that, as soon as ‘Alarm Clock’ dropped, they said there was such a lack of evidence, that I needed to leave. It was nonsense. My application was jam-packed with a lot of evidence in terms of me being in the country and when I entered the country. Things like parents’ evening’s letters. I even had a letter from my headteacher in primary school, who was in retirement at the time. But once I reached out, he said ‘yeah, of course, I’ll write a letter to support the application’, and he said, ‘he was here from Key Stage 2, I had him as a Year Two student’. In their mind, they’re saying I wasn’t here that young. I showed them pictures from my primary school, pictures of me performing in the Royal Albert Hall at like 10 years old. But none of that stuff mattered to them, then the result of that, was basically me getting sent back.

How did you deal with having to start an entirely new life in Jamaica?

It was a process bro, I’ll be honest with you. There were days when I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Upon landing, I didn’t know where I was going to stay that night. I didn’t have any connections to anybody, even though I was born there, I wasn’t in touch with my family out there. So I literally had to start from scratch while being out in Jamaica. I built everything from scratch. I had to research and find family members, get to know them and learn to trust them, loads of trial and error. It was a crazy experience, but it’s an experience that’s made me the man I am today. I’m just fortunate that I was able to make it out the other side. I know a lot of people who were sent out to Jamaica either before or after me and have lost their lives because there was no care and consideration into where they being sent back to. Where I’m from in Jamaica, I’m from an active place in terms of violence. There was a lot of war going on. I’m just fortunate enough to be able to survive through all of that and make it back to the UK, but unfortunately, a lot of people don’t, so it was a journey, man.

Were you allowed to visit the UK temporarily while you were in Jamaica?

I could’ve been allowed to visit, but I didn’t want that route. If I showed them I’m happy to visit, they might’ve said ‘okay well you can continue visiting’, rather than actually allowing me to return. So it was a sacrifice that I took, but it was a hard sacrifice to make. There were times when I really needed my people around me, times when it was really difficult. But I just had to sacrifice being alone during that time, so that in the long-term, I wouldn’t be alone.

How have things been for you since returning to the UK? Has the transition back to London been smooth?

It was a funny transition. I returned to the UK as an older man with a lot more life experience. The scene had changed, everything had changed. The fan base that had grown up with me are now obviously older, my little brother is now a big man, I returned as a father. Relationships that were broken over the years as well through fighting this situation, friendships that were damaged, family relationships that were damaged. There were a lot of things to readjust to, it wasn’t a simple thing. One thing that helped was, during those five years, I planned what I wanted to do when I got back and how I wanted it to be. With those plans, I had to readjust a lot of them once I actually got here. One idea I had was once I arrived, I was going to make a big thing of it, with billboards etc, but when I got here, I felt like ‘you know what, I was robbed of time with my family for five years’. There were family members I wasn’t able to see in those five years, so I wanted to separate the business from the personal. When I arrived, I didn’t announce I’d arrived for at least seven months while I spent quality time with my family, and planned from being on this side. It was easy to plan in Jamaica, but once you’re actually here, it’s a different ball game. The adjustment was something I had to take my time with.

In football, they say you can never prepare for ‘cup final moments’…

Literally! The manager can say this or that, but he can’t control the nerves that running through your body. You know that on a normal day, in a penalty shootout, you’re hitting that top-right hand corner. No problem. Everyone knows you won’t miss. But you can’t plan for the nerves that will be in your system when you run up and kick that ball.

Featured in ‘The Intent 2’, how did that opportunity come about?

What ended up happening while I was in Jamaica was, I started becoming something of a bridge between the UK and Jamaica. Whether that was organising collaborations for artists, whether that was, when artists get there, orchestrating their itinerary. If they wanted to shoot music videos, then I’d link them up with production companies, accommodation, transportation. Then through that, Nicky and Femi, who directed The Intent, were out in Jamaica location scouting. They said they put a role in the film specifically for me and If I’d be interested in it. Once I heard the role and spoke about the logistics, I told them I’m more than willing to help out with anything else they needed on the ground, then we made the movie happen. It was a good moment for me. Because within that time, I was able to link with Ghetts and just be amongst people that I was amongst when I was in the UK. So for a second, it felt good. It felt good to be acknowledged as well whilst I was out there. But it was bittersweet, even with family members. The sweet is when you’re around them but the bitter is when they’re leaving because you’re reminded that you can’t leave with them. I enjoyed every moment of filming the film.

Worked with Steel Banglez back in the day. Talk about how that relationship came about and if there’s anything in the pipeline coming soon…

Me and Banglez originally linked through Young Meth, one of the artists which I did the joint project with. When Banglez met me, I was young, hungry and still in the streets. As much as I was young, hungry and still in the streets, he could see that I didn’t want to stay there. He could see that I have the drive for what I was doing. So we bonded together and we were able to make great music because I can be vulnerable around him in the studio. A lot of people say a lot of things in their music but they don’t really live it. With Banglez, he saw it first hand. He heard me rap about something in the studio, then by the time we leave, my phone’s rang and he can see that situation actually playing out in real-time. In terms of if there’s anything in the pipeline, 100%. We got some stuff coming, for sure, for sure.

What made you want to change your name from ‘Cashtastic’ to ‘Cashh’?

Basically, this whole situation for me has been a full circle. I was born in Jamaica, grew up in the UK, then the full circle ended up back in Jamaica then another full circle back to the UK. When I started, my name was Cashh, it wasn’t Cashtastic. My real name is Cashief, so if you take the ‘ief’ off, you just have Cash.

It’s interesting you say that, because I always hear you refer to yourself as ‘Cash’ in your music rather than ‘Cashtastic’…

Yeah I never refer to Cashtastic. When I first started doing music and it was all street shit, it was under that name. This is the next thing now. Once I started to apply for my stay within the country, that was also a transition within my music. If they’re just listening to the music and not understanding the person, all they’re going to hear is just loads of violence and not understand why I’m even speaking like that. Once I put out music under Cashtastic, that’s what started blowing up, so the name stuck. Then over time, it felt like the right time to come full circle again and mark a new moment. I feel like I outgrew the name Cashtastic in itself. I’m not offended if people still call me Cashtastic, but most people call me Cashh anyways, then through music, they know me as Cashtastic.

Your Daily Duppy showed everyone your pen game had got sharper. Did you expect the strong response you got?

Like I was saying earlier, when I got back to the UK, I had to readjust my plans. The Daily Duppy was supposed to be the second thing that I did, instead of the first. But towards the end of the planning campaign, I decided to do the Daily Duppy first. I felt like a lot of people who might’ve stopped listening to me over the years, I wanted them to hear my pen game and show them how my pen game has increased. The rap Cashh is very much still here. In terms of my song making ability, whether that’s through melody, structure and putting music together, that’s also become a lot stronger. For me, it’s about being at their necks and showing them my bars. When I first wrote it, I knew it would get good feedback but when I saw the edit, the edit was ridiculous. They went overboard with the edit, which was a great thing for me. the editor was actually a Cashtastic fan. I recorded it a few days before I was back, so he and everyone had to sign a non-disclosure agreement and all of that, but the editor was gassed to be apart of Cashh’s return, so he went overboard with it and I’m so appreciative for what he did. So once I saw that and saw how the visuals matched with the bars, I thought I’d get a decent reaction, but I didn’t think it was going to take off as quickly as it did.

Do you feel like you get your credit for helping UK rap to grow, away from being strictly gangster rap to a more vulnerable place?

I don’t think I do. Behind the scenes I do. But publicly, I don’t think I do. I’m not saying I’m the only one that raps about pain, but I was known as a ‘pain rapper’. I became known as someone who says it’s cool to speak about that side of stuff and it’s cool to be vulnerable. Behind the scenes, people tell me how I laid down the blueprint, but publicly, no, I don’t feel like I get it. But I’m aware of it. But the reason why I don’t get it is because of the time that I was away. If I was here, I would’ve been growing with each generation. Since I’ve been back, new fans have found my music, but they think I’m a brand new rapper. There’s also the fact that I was one of the first to rap on dancehall beats. That’s another thing I believe I helped to pioneer. With UK rap, it was very UK rap, people were rapping over a lot of American beats around and people did a lot covers. But in terms of dancehall beats and including a Jamaican influence in UK rap, we definitely helped play a part in that for sure. For me, rather than look at it as negative, I look at it as, as long as I’m still here to have the opportunity to continue my legacy, that’s all I need to focus on.

How has the coronavirus situation impacted your work/ how have you adjusted to this lockdown?

I only returned to the UK in 2019, so you know my 2020 plans were crazy! My 2020 plans were crazy, so lockdown has impacted that a lot, in terms of how frequently I need to release music. I want to release as frequently as possible. It’s not like I don’t have music, I have five years worth of music to release. There’s music that I didn’t release while I was in Jamaica because I needed to save it for when I had more listeners. In terms of releasing one song every three months, I’m not on all of that. I firmly believe that you get what you put in. That generation who aren’t fully aware of who I am yet, I want to work, to grab their ears. I don’t want someone to tell them to listen to me, I want to put work in and let them find my music. So we haven’t been able to go out and shoot as many videos as we needed. I also haven’t dropped a project, because I want to release more music from the project, leading up to it. Then in terms of not being able to do shows and festivals, it’s definitely had an impact. But because I had a plan, I’ve just been able to rearrange around it, so it’s not like I’ve been helpless completely. During the lockdown, I dropped ‘Trench Baby’ and still been able to keep the fire burning a little bit. Now as the lockdown eases, we’ve got ‘Trouble’ out right now and we’re going back to the plan of releasing as frequently as possible.